Rose Piper, a celebrated African American painter, was born in New York City in 1917 and raised in the Bronx. Piper received a BA as an art major and geometry minor from Hunter College in 1940, and then went on to study at the Art Students League from 1943 to 1946. Growing up, Piper developed an interest in African American history and folklore from the stories her parents told her about life in the South. With encouragement from a friend, poet Sterling Brown, Piper delved into listening to and studying African American records.[i] Using blues music as her inspiration, in 1946 piper applied for and received a Rosenwald fellowship—to do a series of paintings portraying urban and rural African Americans as African Americans depict themselves in blues songs.[ii] The exhibition, “Blues and Negro Folk Songs,” which illustrated African American life in a style that mirrored the style of blues, appeared at New York’s Roko Gallery from September 28 to October 30, 1937.

Rose Piper, a celebrated African American painter, was born in New York City in 1917 and raised in the Bronx. Piper received a BA as an art major and geometry minor from Hunter College in 1940, and then went on to study at the Art Students League from 1943 to 1946. Growing up, Piper developed an interest in African American history and folklore from the stories her parents told her about life in the South. With encouragement from a friend, poet Sterling Brown, Piper delved into listening to and studying African American records.[i] Using blues music as her inspiration, in 1946 piper applied for and received a Rosenwald fellowship—to do a series of paintings portraying urban and rural African Americans as African Americans depict themselves in blues songs.[ii] The exhibition, “Blues and Negro Folk Songs,” which illustrated African American life in a style that mirrored the style of blues, appeared at New York’s Roko Gallery from September 28 to October 30, 1937.

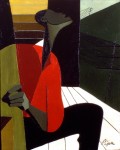

The exhibition was her first and had great success. Among the twelve pieces inspired by blues and folk themes was Slow Down Freight Train, a portrayal of notable blueswoman Trixie Smith’s song “Freight Train Blues.” [iii] In the early twentieth century, many African Americans migrated North in search of economic opportunity and in hopes for a better life. Industrialization in the North opened up a variety of industry and factory jobs that were promising for African Americans. This plight of African Americans became known as “The Great Migration,” and Slow Down Freight Train offers a snapshot of this experience. The painting delineates a lone man in a freight train car leaving his family behind in his migration northward. The experiences of the great migration inspired many blues songs including “Freight Train Blues” by Trixie Smith. Smith puts the pain that women feel when their man leaves them behind into lyrics. Piper titled her painting Slow Down Freight Train after Smith’s song, as “a woman’s plea for the train to slow down so she might go along with her man.”[iv] It is unique that Piper chose to depict the migration from the woman’s perspective, viewing her man leaving, as opposed to Smith’s perspective of the woman suffering. By portraying the experience from the woman’s perspective and viewing the man in pain, it empowers women and demonstrates the strength they had to find when left behind. Scenarios of role reversal were popular in the 1920s as it supported the growing image of the “new woman,” who was strong and independent. Piper embodies this belief by showing a man’s vulnerability in her painting.

In the early twentieth century, women dominated blues recordings. However, men sang blues too, they just were not recorded and the streets were often their venue. Within the context of blues, the man in the painting’s open body posture and position of his left hand suggests that he could be playing a single stringed instrument. Make shift and home made single stringed instruments were popular in African American communities in the south and were the foundation of the blues[v]. The strong lines in the painting draw the viewer’s attention to his left hand, which is illuminated by highlights. The attention drawn to his left hand and face frames that could be plucking a single stringed instrument and singing the blues as the freight train takes him away from home.

While the painting portrays pieces of blues culture, the subject matter is mainly symbolic of The Great Migration. In order to respectfully portray the raw emotion of the migration, Piper uses a semi-abstract expressionistic style comparable to cubism. The elongated neck, attenuated figure of the man, and turned head suggests a sense of agony and longing the passenger of the freight train feels. Piper’s formal education in geometry is evident in the painting with the deliberate use of lines and shape for emphasis. The lines on the floor boards, the back wall panels, and the slope of the hill with telephone wires all point to the man’s hidden face which emphasizes the unfair burden of the African American experience. The telephone wires on the landscape are also symbolic of the distance growing between himself and his family and the therefore increasing difficulty of communication. The telephone wires foreshadow that he is heading north to an unfamiliar urban environment to work in a factory, which is a sharp contrast from his home in the rural south.

Themes from blues songs, like difficulty of migration, were a catalyst for Piper to capture the struggles of the African American experience of the early 20th century. Piper used her artistic gift and training to simultaneously work on a political agenda—“to help erase segregation, ridicule, humiliation and violence.”[vi] Piper painted her blues and folk themed exhibition in the late 1940s, which was a time period where racism and Jim Crow Laws were at their highest. In calling attention to the plight of African Americans, Piper was slightly ahead of her time, considering the civil rights movement did not truly begin until 1955. Unfortunately Piper never painted during The Civil Rights Movement due to financial burdens and the need to take care of her family. Familial obligations forced Piper to give up painting and transition into a more financially promising and stable job in the textile industry. Piper worked in the garment industry beginning in 1952 as a designer and stylist working specifically with knit wears.[vii] When she resumed painting in 1980, she painted with much greater precision and detail than ever before. This increase in precision was a direct result of her work with textiles, which requires much attention to texture and detail. However when she took up her brush again, the themes of her paintings remained the same, still finding inspiration from African American folklores to portray facets of the African American experience.

HLM

[i] Lock, Graham, and David Murray, The Hearing Eye: Jazz & Blues Influences in African American Visual Art. (Oxford; Oxford UP, 2009), 48.

[ii] Rose Piper, “Statement of Plan Work,” 1945, Julius Rosenwald Fund Collection, Box 440, Folder 20, Fisk University Library, Nashville, Tennessee. Quoted in Schulman, Daniel, and Peter Max. Ascoli, A Force for Change: African American Art and the Julius Rosenwald Fund. (Chicago, IL: Spertus Museum, 2009), 73.

[iii] Lock, Graham, and David Murray, The Hearing Eye : Jazz & Blues Influences in African American Visual Art. (Oxford; Oxford UP, 2009), 52

[iv] Piper, letter to Charles Millard, 1 August 1990, Ackland Art Museum archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Quoted in Lock, Graham, and David Murray, The Hearing Eye: Jazz & Blues Influences in African American Visual Art. (Oxford; Oxford UP, 2009), 52.

[v] William Barlow, Looking Up at Down: The Emergence of Blues Culture (Philadelphia: Temple, 1989). 30-31.

[vi] Lock, Graham, and David Murray, The Hearing Eye : Jazz & Blues Influences in African American Visual Art. (Oxford; Oxford UP, 2009), 49.

[vii] Kathryn Piper, “Rose Piper,” Curatorial Files, Ackland Art Museum Archives, Chapel Hill, NC.