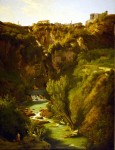

Man has always had a mutual relationship with his surroundings, the environment, and all that the natural world has to offer. This exchange is one that Pierre-Athanase Chauvin’s The Falls at Tivoli with the Temple of the Sibyl displays quite distinctively. The earthly color scheme oscillates between the light blue skies, deep green vegetation, and warm tones of the earth and buildings, suggesting that man and nature can live together harmoniously. Other aspects of the painting, however, imply that humans and the environment are not coexisting peacefully. These interactions are, perhaps, indicative of how a classical interpretation of 17th century landscapes display a harmonious and peaceful theme in paintings.

Probably because he excelled during the early 1800s, a period of idealism and neoclassicism, Chauvin was an idealist who tended to sway toward the classical approach to painting [1]. Classicists were commonly formal and very limited in terms of how much creativity they would show in their works. Instead of being radical in any way, artists would keep to a more reserved form of painting landscapes. Specializing in landscape, Chauvin’s favorite scenes were of both historical and actual subjects. His works sometimes depicted beautiful and realistic mountains, all types of lush, dark green vegetation, contrasted with a light blue sky. And other times, his paintings included ancient buildings, like those of the Greeks or Romans. [2]It is with these common neo-classicist and idealist techniques that The Falls at Tivoli with the Temple of the Sibyl attempts to display the give-take relationship between man and nature.

The first cues that men and mother-nature do not live peacefully together are the buildings that dwell on the mountain tops as well as in the middle-ground of the piece. The buildings are striking, and impressive examples of western architecture, but they seem to be tainting the peak’s natural allure. In retaliation to human activity on the mountain tops, the environment encroaches on the rubble in the middle-ground of the painting. By depicting the architectural remains have been overpowered by a flourishing overgrowth of vegetation and nearly eliminating any evidence that man once occupied the area, Chauvin shows that nature is not passively allowing man to harm the environment. Earth and mankind are fighting for dominance in Chauvin’s artwork.

While human inhabitance causes conflict for the natural world, the two can, in reality, interact side by side in a peaceful way. When referring to the buildings once more, they do indeed obscure the majesty of the peaks. However, Chauvin makes an effort to show the buildings lying within the natural flow of the mountainous landscape, instead on top of the soil, polluting the mountain, in a sense. The structures were successfully placed within the mountain’s curves and provided an aesthetically pleasing sight.

Lastly, the presence of the man in the foreground shows how well man cannot only benefit from, but also how thoroughly enjoys nature and its products. Chauvin painted the man leisurely walking back from the pools of the waterfall, fishing rod in hand to show that it is possible that men can actually have a healthy relationship with nature. Indulging in its plentiful resources for survival is common, but those same resources can be used for leisure as well. In any sense, the man in the foreground is getting along with nature far better than the men who constructed the buildings on the mountain peaks. That is clear.

In all, Chauvin is a French landscape artist who thrived by reproducing the neo-classical aesthetic popular during his lifetime. With realism, deep colors, and some color contrast, Chauvin helps to share the story of how nature and mankind came together. Men began on this world in a peaceful relationship with Earth. Mankind without immense leaps in technology, industrialization, and radical population growth were not as harmful to the environment. But with societal and cultural advances, men soon took advantage by, according to Chauvin’s piece, for instance, building on mountain peaks and creating unnecessary blemishes in the landscape’s natural beauty. Although the environment does retaliate in a way, mankind eventually will either come out victorious or man and nature’s relationship will completely over in the beginning peaceful stages.

A.G.O.

[1] Peake, Lorraine. “Chauvin, Pierre-Athanase.” 2007. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T016190?q=Pierre-Athanase+Chauvin&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit (accessed April 3, 2011).

[2] Rosenberg, Pierre. French Painting 1774-1830: The Age of Revolution. Frederick J. Cummings, Pierre Rosenberg, Robert Roseblum. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.

References

Lagerlöf, Margaretha R. Ideal Landscape. New Haven: Yale University, 1990.

Peake, Lorraine. “Chauvin, Pierre-Athanase.” 2007.http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T016190?q=Pierre-Athanase+Chauvin&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit (accessed April 3, 2011).

Rosenberg, Pierre. French Painting 1774-1830: The Age of Revolution. Frederick J. Cummings, Pierre Rosenberg, Robert Roseblum. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.