Growing up during the post-Mexican revolution in the 1920’s, Leopoldo Méndez was very active in the politics of the time. One of his main concerns was social and political injustice, not only in Mexico, but around the world. Méndez and his other colleagues were very interested in representing the widespread fascism movement in other countries, and felt the need to warn people about the detrimental effects of this style of government.[i] In this effort, Méndez was responsible for founding two very important Mexican art organizations: The League of Revolutionary Artists and Writers (LEAR), and People’s Graphic Art Workshop (TGP).[ii] He was also a part of the Estridentismo (Stridentist) movement, which was an art movement that was formed from other art forms, such as cubism and ultraism, which also incorporated a social aspect of that time period.[iii] This movement was a reflection of the politics during the Mexican Revolution.

Growing up during the post-Mexican revolution in the 1920’s, Leopoldo Méndez was very active in the politics of the time. One of his main concerns was social and political injustice, not only in Mexico, but around the world. Méndez and his other colleagues were very interested in representing the widespread fascism movement in other countries, and felt the need to warn people about the detrimental effects of this style of government.[i] In this effort, Méndez was responsible for founding two very important Mexican art organizations: The League of Revolutionary Artists and Writers (LEAR), and People’s Graphic Art Workshop (TGP).[ii] He was also a part of the Estridentismo (Stridentist) movement, which was an art movement that was formed from other art forms, such as cubism and ultraism, which also incorporated a social aspect of that time period.[iii] This movement was a reflection of the politics during the Mexican Revolution.

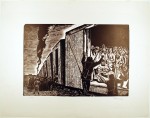

Political and social ideas were reflected in many of his works, including Deportation to Death (Death Train). In this particular work, he portrays the anguish and torture of those who were a part of the Holocaust. The piece was created in 1942, while the Nazis were at the height of their reign. Méndez’s work aimed to expose the horrific Nazi crimes being committed in Germany on an international level.

The Holocaust is commonly known as the genocide of Jews, which occurred in Germany under the rule of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party. It took place during World War II, when communism and fascism were on the rise in many of the large, well-known countries such as Germany and the Soviet Union. Méndez, known for creating pieces of art that represented world events, was not for fame and fortune, but more so for the benefit of society. The linocut print Méndez created shows a long, immeasurable train packed full of people being taken away to concentration camps. The billowing smoke coming from the train’s engine signals to viewers the ominous fate of so many victims of the Nazi Holocaust that were sent to their deaths in gas chambers and their bodies disposed of in crematoriums. There are not many similarities in the faces of those aboard the train at all, except that they all have an expression of fear and sadness. There are men, women, and children of all ages aboard the train. The piece shows how families living in Germany at the time were torn apart and taken away from their domestic lives against their will. They were forced to leave their spouses and children only to be put into boxcars and shipped off to work and die like animals. The only family they were left with was those on the train with them, who would likely die as well, although some did survive the horrors of the camp. The fact that there are multiple boxcars in the piece, even though you cannot see inside of them, suggests that there were an infinite number of people being treated this way. It makes it seem like this was a common, everyday thing, which is extremely anomalous compared to the lives of people living in Germany today.

The whole linocut within itself just puts you in the realm of the Holocaust, and it gives you the feeling of what it must have been like. Everything is dark, in black and shades of grey. Although it could possibly be daytime, the sky is black and filled with smoke and foreboding, adding to the uneasiness Méndez imbues in the scene. There are men forcing people on the train dressed in all black with guns in their hand. In contrast to the dark demeanor of the Nazi assailants, the victims they force on the train appear to be lighter, whiter, perhaps suggesting a bleak division of good and evil. The piece instills in the viewer similar emotions of those aboard the train, allowing you to feel this death sentence forced upon their lives. Méndez wanted to make the viewers feel this way so that hopefully they would be inspired to take action, which directly relates to the political groups and stridentist movement he was involved in. The intention of the piece basically sums up Méndez’s life work, which was to create art that motivated others to take a stand against the political corruption of the world.

CMW

[i] Caplow, Deborah. Leopoldo Méndez: Revolutionary Art and the Mexican Print. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 125.

[ii] Leonor Morales. “Méndez, Leopoldo.” In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T056797 (accessed April 11, 2011).

[iii] Elisa García Barragán. “Estridentismo.” In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T026832 (accessed April 26, 2011).